Originally Published 15 August, 2010

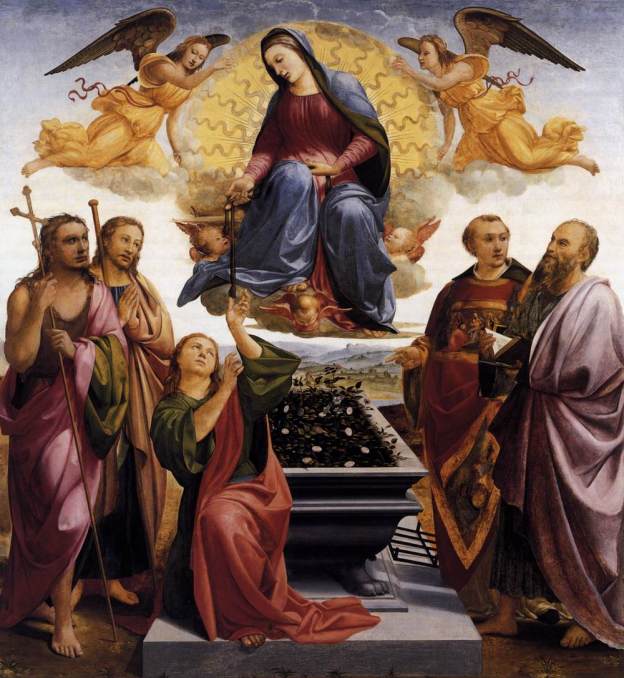

The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary is a dogma of the Catholic faith, solemnly declared as a dogma ex cathedra by Pope Pius XII in the document Munificentissimus Deus on 1 November 1950. This Dogma teaches formally that Mary, was assumed, body and soul into heaven at the end of her earthly life and that her body did not suffer corruption.

This dogma is among what are called the “negative prerogatives” of the Blessed Virgin, because they are lacking a certain defect. As the Immaculate Conception lacks original sin, so the Assumption lacks bodily corruption. We see also a strong connection between this doctrine and the Immaculate Conception which was also solemnly declared ex cathedra by the Pope, whereas the other Marian dogmas were confirmed by early councils. Pope Pius XII taught in his solemn definition:

“And, although the Church has always recognized this supreme generosity and the perfect harmony of graces and has daily studied them more and more throughout the course of the centuries, still it is in our own age that the privilege of the bodily Assumption into heaven of Mary, the Virgin Mother of God, has certainly shone forth more clearly.

That privilege has shone forth in new radiance since our predecessor of immortal memory, Pius IX, solemnly proclaimed the dogma of the loving Mother of God’s Immaculate Conception. These two privileges are most closely bound to one another. Christ overcame sin and death by his own death, and one who through Baptism has been born again in a supernatural way has conquered sin and death through the same Christ. Yet, according to the general rule, God does not will to grant to the just the full effect of the victory over death until the end of time has come. And so it is that the bodies of even the just are corrupted after death, and only on the last day will they be joined, each to its own glorious soul.

Now God has willed that the Blessed Virgin Mary should be exempted from this general rule. She, by an entirely unique privilege, completely overcame sin by her Immaculate Conception, and as a result she was not subject to the law of remaining in the corruption of the grave, and she did not have to wait until the end of time for the redemption of her body.”[1]

Moreover, the Fathers at the First Vatican Council, beseeched Bl. Pius IX for a solemn definition by drawing the same theological link with the Immaculate Conception in the Protoevangelium (which is Genesis):

“According to the Apostolic teaching [recorded in Rom. V,8; I Cor. XV, 24, 26, 54, 57, Heb. II, 14, 15 and other texts] when Jesus triumphed over the Ancient Serpent (Satan) He gained a threefold victory over sin and its effects, i..e concupiscence and death. Since the Mother of God is associated in a singular manner in this triumph with her Son, (Gen. III:15), which is also the unanimous opinion of the Fathers: we do not doubt that in the aforementioned [Scriptural] passage this same Blessed Virgin is pre-signified as illustrious by that threefold victory: over sin by her immaculate conception, over concupiscence by her virginal motherhood, and in like manner over hostile death by a triumphant resurrection similar to that of her son.”[2] In fact, had it not been so, as the theologian Joseph Pohle makes the observation that death would in fact have triumphed over Mary had she suffered bodily corruption.[3] Mary triumphs rather with her Divine Son and through His redemptive work over death completely.

The Death of the Blessed Virgin

While the dogmatic definition of Pius XII teaches that Mary was assumed body and soul into heaven, it does not teach explicitly on the manner by which Mary died. So the discussion about the death of the Blessed Virgin is not subject to the dogmatic definition per se. Based on this there are certain theologians who run around today saying that because Pius XII did not specifically address the manner of Mary’s death, that there is no proof that Mary died and thus claim she is immortal. At the time of the definition there were likewise some who pointed to it as proof of there position. The first one known to have suggested Mary’s immortality is St. Epiphianus, yet he does not deny it either and as Cardinal Baronius suggests, he was merely defending Mary’s virginity against impious heretics by saying Scripture does not even say if she died. There were some 4th century traditions holding to Mary’s immortality, and more recently the theologians Roschini and Gallus (pre-Vat.2) advocated this position. Roschini maintained, that since Munificentissimus Deus makes no mention of the death of the Blessed Virgin, the number of those holding to Mary’s immortality will increase.[4]

This is not the case however, as the common opinion of the Church provides a moral unanimity that Mary in fact died, and that those who claim otherwise actually deny the teaching authority of Tradition. The reason is, as Alastruey notes is that “[it] is immediately connected with the revealed truths concerning original sin and the general economy of the redemption of the human race. Therefore the question of the Virgin’s death is not a matter of opinion nor a pious belief which can be disputed freely; it is a firm and consistent teaching which should be venerated for its antiquity.”[5]

Moreover St. Ephrem (doctor of the Church) states explicitly that Mary was a virgin all her life and died a virgin. St. John Damascene points out that as her son did not refuse to die, neither did she. St. Andrew of Crete “She who made heavenly the dust of the earth laid aside the dust of the earth; she put aside the covering which she received through generation and returned to the earth what is of the earth.” St. John of Thessalonica says that the all-glorious Virgin Mother of God, after spending some time with the apostles until they by command of the Holy Ghost, had spread throughout the world to preach the gospel, left the earth by a natural death. St. Modestus of Jerusalem gave his first sermon on the death of the Blessed Virgin.[6] The Greek word used to describe the Assumption is κοίμησις, which means literally “falling asleep” and when used with reference to the end of someone’s life, as in English (eternal rest) it means death. This word not only appears in the Greek liturgy but is used by all the Greek Fathers to speak of the Assumption.

Furthermore, most theologians teach that Mary did in fact die. Merklbach calls it a certain teaching, lest the mother should be seen as greater than the son.[7] The Theologians Billuart and Novato treat the death of the Virgin as certissima.[8] Most other theologians, particularly Roman Theologians who treat the subject concur.

Moreover, Mary’s death is affirmed by the ancient liturgy of the Assumption in the Roman missal, which reads: This festival of the day, O Lord, being venerable to us, on which the holy Mother of God suffered temporal death, but still could not be kept down by the bonds of death who has begotten Thy Son our Lord incarnate from herself.”[9] An 8th century chant from the Chaldean Church likewise affirms: “Admirable in her mortal life, marvellous in her life-giving death, living she was dead to the world, dying she raised the dead to life. The apostles hasten to her from distant lands, the angels descend from on high to pay her honour due.”[10]

Yet, if Mary did in fact die, does this not mean that she was subject to original sin in some manner? No it does not in two ways. Firstly, Mary did not suffer corruption, so that if there was a temporary separation of body and soul, (the matter of death) her body did not rot in the grave, but as Our Lord’s remained inviolate so that when her soul reunited with it she was assumed straight to heaven. Secondly, though it was not necessary for Mary to die at all, since not being conceived with original sin, she was not subject to its affects, it was fitting.

Merklbach teaches further in his work on Mariology that: “Christ voluntarily subjected himself to the law of God commanding death, and also by his suffering and death redeemed the human race from sin, Mary also, having cooperated in the work of redemption, ought to, as Christ, suffer and die and also subject herself to the command of death.”[11] St. Albert the Great taught that Mary died from a longing of love so powerful that she could not bear separation from her Son and Saviour. While the exact manner of the death is unkown to us, it is clear that Mary did in fact die, and this death was completely fitting since it modeled the path our Lord took also.

The Dogma in Tradition

Sometimes Catholics who have no grasping of the Tradition will assert, as it is sometimes done for the Immaculate Conception, that there was no doctrine of the Assumption or no Mass for it and that the Pope just declared it ex cathedra. I once met a priest who argued that we could create new masses, after all there wasn’t a Mass for the Immaculate Conception or the Assumption prior to the dogmatic definitions. This however could not be further from the truth. In fact, some object to the dogma (including Protestants) claiming that since it was only declared in 1950 it can’t really be of tradition.

This dogma is not only very old liturgically, it is of ancient origin. Though good theological arguments can be presented in favor of this doctrine, it is primarily in Ecclesiastical Tradition that we have the most verification of the truth of this doctrine outside of the Solemn Definition of Pius XII.

East and West Fathers and Doctors of the Church supported it, from the 5th century on to the present. In the beginning there were several apocryphal stories, one which is most famous being that of Pseudo-Dionysius who claimed that all the apostles had gathered for Mary’s death, and the Church denied the authenticity or even condemned some of these over time. Yet, the continual faith in the Assumption has continued east and west in unbroken succession since the 5th century, which helps to prove that the sensus fidelium was not based on the apocryphal legends since it persisted when their authenticity was called into doubt. In the 6th century the Eastern Emperor Maurice had ordered the feast of the κοίμησις to be celebrated each August 15th in Constantinople, and just as so many Eastern Fathers (most notably St. Andrew of Crete and St. John Damascene) have preached in favor of the Assumption, so the Eastern Church even out of communion with Rome has maintained this feast. In 1672 at Jerusalem the Orthodox Churches confessed in a council “Though the immaculate body of Mary was locked in the tomb, yet like Christ, she was assumed and migrated to Heaven on the third day.”[12] St. Gregory of Tours had taught “The Lord commanded the Holy Body of the Blessed Virgin to be borne on a cloud to Paradise, where, reunited to its soul, and exulting with the Elect, it enjoys the never ending bliss of eternity.”[13] The writings in the East of St. Sophronius, St. Andrew of Crete, St. Fermanus and most preeminently St. John Damascene serve as foundational witnesses in the East, while this doctrine flowered in the West through the Latin Fathers and theologians, decoratively adorned in all the Western Liturgies, and wonderfully attested to in Pius XII’s document examining the Tradition on Our Lady’s Assumption. This is a sign for us that even when the Pope speaks ex cathedra, he is not making new doctrine, neither does he recklessly declare the opinion of the day, but prudently and eruditely examines all the factors, histories, traditions etc, and Pius XII shows us this in Munificentissimus Deus where does not cite only the theological arguments such as that presented at Vatican I, no matter how good it is, he carefully went over the whole tradition, because we are not a Church of the theological opinions in sway today, but a Church of tradition which believes what has always and everywhere been believed by those professing divine and Catholic faith.

[1] Munificentissimus Deus, nos 3-5

[2] Quum iuxta apostolicam doctrinam {Rom. V, 8; I Cor. XV, 24, 26, 54, 57; Heb. II, 14, 15) aliisque locis traditam triplici victoria de peccato et de peccati fructibus: concupiscentia et morte veluti ex partibus integrantibus constituatur ille triumphus, quem de satana, antiquo serpente, Christus retulit, quumque Gen. III, 15 Deipara exhibeatur singulariter associata Filio suo in hoc triumpho accedente unanimi SS. Patrum suffragio: non dubitamus quin in praefato oraculo eadem B. Virgo triplici illa victoria praesignificetur illustris adeoque non secus ac de peccato per immaculatam conceptionem et concupiscentia per virginalem maternitatem, sic etiam de inimica morte singularem triumphum relatura per acceleratam ad similitudinem Filii sui resurrectionem ibidem praenuntiata fuit. (Collec. Lacensis, vol. VII, pg. 869)

[3] Pohle-Preuss, Mariology, pg. 114)

[4] Roschini, Il Problema della morte di Maria SS. Dopo la constituzione dogmatica Munificentissimus Deus

[5] Alastruey, The Blessed Virgin Mary, vol. 1, pg. 253

[6] Encomium in B.V; PG, LXXXVI, 3280

[7] … “B. Virgo fuierit morti subjecta, ut Filio suo conformaretur, nec Matris potior quam Filii conditio videretur.” Merklbach, Mariologia, pg. 266

[8] Novato, De eminentia Deip. Virg. Mariae, II, c.8; Billuart, De myst. Christi, diss. 14, art1-2

[9] Veneranda nobis, Domine, hujus est diei festivitas in qua sancta Dei genitrix mortem subiit temporalem, nec tamen mortis nexibus deprimi potuit, quae Filium tuum Dominum nostrum de se genuit incarnatum.” (Migne, P.L., LXXVIII, 133)

[10] Gureranger, The Liturgical Year, vol. 13, pg. 388

[11] Christus voluntarie debebat se subiicere legi Dei mortem statuenti, atque passione sua et morte genus humanum a peccato redimere, Maria quoque, in opere redemptionis consociata, sicut Christus debebat pati et mori, atque mandato mortis se subiicere. Quod fecit consentiendo in hoc quod esset mater Dei-Redemptoris, Merklbach, Mariologia, pg. 267-268

[12] Pohle, Mariology pg. 116

[13] Dominus susceptum corpus sanctum in nube deferri jussit in paradisum, ubi nunc resumpta anima cum electis ejus exsultans aeternitatis bonis nullo occasuris fine perfruitur. Migne, P.L., LXXI, 708)

I am currently raising money to translate St. Robert Bellarmine’s works into English (works which have never been in English). This is a daunting task and requires my full time energy. It also means acquiring the funds to pay for bills and food while doing this. So this is why I have decided to raise the money to maintain myself translating. The formal site is here.

I am currently raising money to translate St. Robert Bellarmine’s works into English (works which have never been in English). This is a daunting task and requires my full time energy. It also means acquiring the funds to pay for bills and food while doing this. So this is why I have decided to raise the money to maintain myself translating. The formal site is here.